Life, Up Close, in a Ukrainian Village

Growing up, Lida Suchy listened to her parents’ tales of the Ukrainian homeland, which they fled because of Soviet persecution during World War II. At night, her father, Zenon, told her bedtime stories about Baba Yaga, the Ukrainian witch, but also tales from his summers spent among the Hutsul culture, deep in the Carpathian Mountains of western Ukraine. There was even a touch of romance to her parents’ first moments in exile: Zenon met his wife-to-be, Irene, when he pulled her through the window of the last train leaving the station. Together, they watched the sunset.

“These stories had a magical place in my mind,” said Ms. Suchy, who was born in 1960 and raised in North Dakota and upstate New York. “I was really interested in confronting the reality of what was there with myths he had created in my head about what home was like.”

She got the chance to see for herself after the Berlin Wall fell, when she accompanied her father to his hometown, Kolomyia. It was far from magical.

“We found his house,” Ms. Suchy recalled. “It was really, really sad. It had been converted into a chicken coop. We found almost no traces of anyone that he had known from before. The places that he remembered from his youth were almost unrecognizable to him.”

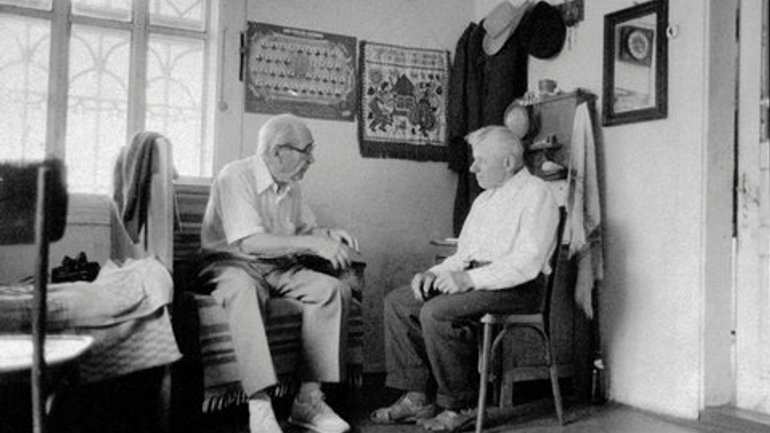

Fortunately, an ethnographer at a local museum recommended they contact Dido Vasyl Potjak, a man living in Kryvorivnya, a couple of hours’ drive away. He was born in the same year as her father, 1911, and the two men hit it off. He became a dear friend and her connection to a village that she has now documented for nearly 25 years. He invited her back for Ukrainian Christmas, and her photographic project “Portrait of a Village: The People of Kryvorivnya Ukraine, 1992-Present” was born.

Her first pictures were taken soon after she learned of a local Christmas caroling ritual in which men travel around the mountains, singing, for two weeks at a time. Ms. Suchy gathered more than a hundred carolers in the village square and made a group portrait that became her introduction to the community. For several years, those villagers saw her hauling around her heavy 8×10 camera, and she feels the locals respected her work ethic, which also helped enmesh her in the community.

“They could relate to that because it was physical labor,” she said. “Many of them toil a lot on land which is not productive, with a short growing season.”

Ms. Suchy spent nearly a decade away from the project, which created the time jumps that allow for her jarring diptychs. We see the dissident Eudosia Sorochan as she grows from old to ancient. Or a father, Dymytro, who looks almost hopeful in 1995, alongside one son, but totally defeated in 2013, sitting next to another.

Then there is a young girl, Irena, who’s standing by the Black Cheremosh River, an inflatable toy around her 9-year-old torso, in 1993. Twenty years later, she is in the same spot, now wearing a revealing bikini with little to hide.

Artists, writers and creative types have long been drawn to Kryvorivnya’s natural beauty, folkloric traditions and remote location. It’s a place of healing, she said, and volunteers from the community have invited wounded soldiers from the war in Ukraine’s east to come convalesce in the village. (Not surprisingly, Ms. Suchy plans to photograph them.)

“I do think that it has something unique,” she said. “It is a magical place for the soul. People come there to heal, to have a peace, and maybe commune with nature.”

Although the project began in the last century, Ms. Suchy is still going strong. She made new images in Kryvorivnya just this summer, supported by a Guggenheim Fellowship, and intends to make a book of the project. As an artist, she hopes her photographs from one small mountain village can help combat people’s limited understanding of Ukraine, a war-torn country on the other side of the world.

“Most of the news coming from Ukraine focuses on the war, the violence, the destruction and extreme problems that are stereotyped. I wanted to show the everyday life of ordinary people,” she said. “I really feel a kinship with them. I would like to transfer, if possible, that sense of touch, that sense of closeness, that I feel with the people.”