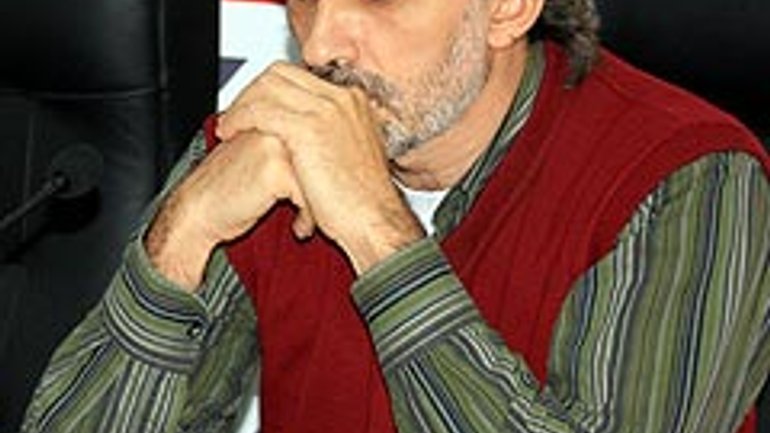

Historian Yaroslav Hrytsak: Historical Memory Needs to Be Accountable

Is the memory of Holodomor Uniting Ukrainians?

Is the memory of Holodomor Uniting Ukrainians?

The memory about the Holodomor unites Ukrainians. This is not a hypothesis or an assumption but a conclusion of sociological research that shows that in the last three years a new phenomenon has appeared in the Ukrainian society—Ukrainians have come to believe that the famine was a genocide. A consensus has risen around this in both the east and west. Of course, the level of consensus is different in different regions: in the Donbas it’s less pronounced than in Galicia. We could discuss why this has happened, but it is an accomplished fact. Aleksandr Tsipko, one of Gorbachev’s advisers during the reforms, believes that Putin’s and the Kremlin’s biggest problem lies in the fact that they think the Holodomor is a Galician fable. In reality, the memory of the Holodomor is in central and eastern Ukraine for it is these territories that experienced the famine. In local families lived personal memories that were silenced; but now, when the famine is being discussed at the state level, both memories—personal and official—overlapped and resonated with one another. Just how stable this memory will be is yet to be seen. There is always the suspicion that that which quickly burns, quickly extinguishes.

We should understand that the collective memory is actually not about the real history and real facts but about what we think about the past. Galicia never experienced the famine. But Galicians are among the group of Ukrainians who “remember” the famine the most and believe that it was a genocide. Our way of thinking is foundationally mythological. Ernest Renan even said that an inaccurate understanding of history is a foundation for the existence of a nation. Galicians remember the famine, though they were not affected by it, because it is part of the national myth. For Galicians this is not a part of their personal history but rather their specific vision of the past in which the Soviet Union was always tied in with repressions and a threat to life.

Is the memory of Victim healthful for the nation?

Victims are an obligatory, often central, element of a collective memory—especially when talking about construing the so-called convenient past. Let’s say the modern Austrians built themselves a myth that Austria was the first victim of Hitler since it was the first to join the Reich. Building a historical memory only as victims carries not only untruth but also a danger because the topos of victims provokes the topos of unaccountability: “We survived, we were oppressed, so now we are allowed everything.” Together with a convenient history arises a convenient space for unaccountable politics and an unaccountable society, which does not want to take responsibility for its actions.

In truth there is no society that was only a victim or only a criminal. Discovering that everything in your history is not in order can be a shock. But this shock can have a therapeutic effect. The classic example is Poland—from generation to generation it was brought up on the topos of a victim (“Poland the Christ of Nations”), Jan Gross in his book “Neighbors.” Discussion of this book was very long and difficult, and in the end the Polish president and the Polish church found the strength to ask for forgiveness for the horrible actions of their fellow citizens. A society should rework its history to produce in itself an antidote against having no memory. The Germans even created a special term—“remaking history.” This method of history is good for reconciling with neighbors. It’s not strange that the Germans succeeded in reconciling with the French and with the Poles. In their turn, the Poles, after the fall of communism, reconciled with all of their neighbors, including Ukrainians. This is a very Christian formula.

What does the Ukrainian society need to heal its memory?

Now we are in need of a Ukrainian-Ukrainian reconciliation. Its success depends on whether politicians and intellectuals who are determined to express this formula appear on both sides. And this means putting into practice the type of historical policy that that I call accountable. So far the discussions on the past in Ukraine are taking place for a different reason: they are creating a smokescreen that masks the inability or the unwillingness of politicians to deal with other problems like the absence of systematic reforms, without which we are slipping into the third world. This is convenient for politicians. They are playing with history, not understanding just how dangerous this game can be. Sooner or later, the manipulator can become a victim of his manipulations as happened with Kuchma in 2004. If our politicians don’t learn to take responsibility, then we, citizens and voters, must do it for them. Because otherwise all of our constructions of the national past can slip away.

Written by Mariana Karapinka